Observing the social interactions and behavioral strategies that New World monkeys share with humans

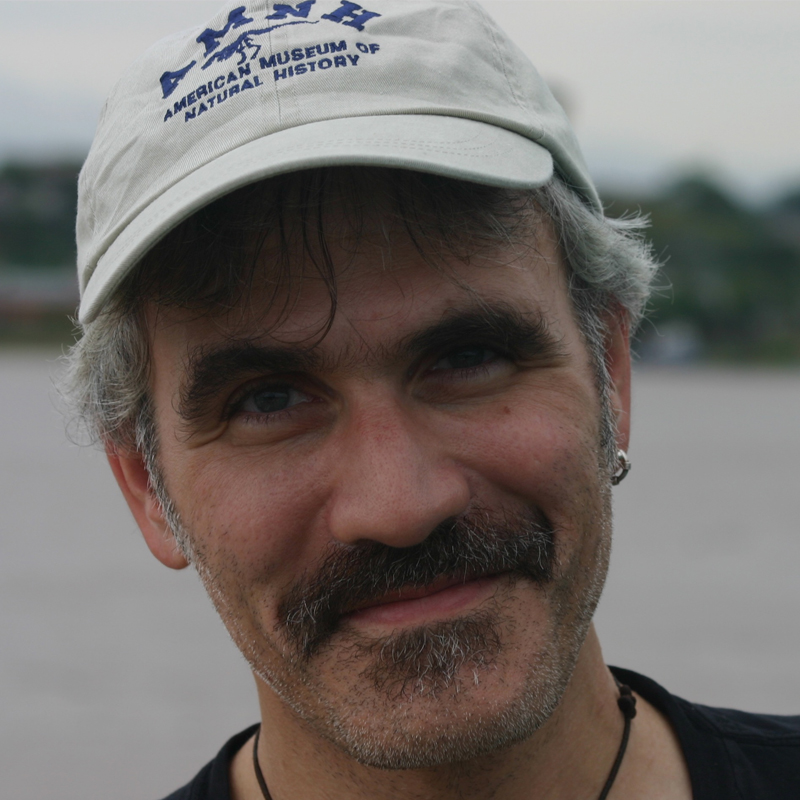

Nonhuman primates, our closest mammalian relatives, have long been studied to understand the evolution and patterns of human social interactions. While our close relatives—chimpanzees and gorillas—are often used as models in such studies, Dr. Anthony Di Fiore, Professor in the Department of Anthropology at University of Texas at Austin, focuses on species from a different lineage of primates from the neotropics, known as the New World monkeys, or platyrrhines. These species are only very distantly related to humans, sharing a common ancestor with us about 40 million years ago. But these New World primates converged independently on some of the same patterns of behavior and sociality that arose in the human lineage. Dr. Di Fiore and his colleagues conduct long-term behavioral and ecological field research on several species of wild primates in the hyper-diverse Yasuní Biosphere Reserve in lowland, Amazonian Ecuador, looking at aspects of social interactions and behavioral strategies they share with humans, including their grouping patterns, mating systems, and patterns of parental care. Studying these topics helps us better understand the ecological and social factors that underlie these behaviors, without the confound of a shared recent evolutionary history.

To get a long-term perspective on what a nonhuman primates’ social system looks like, animals must be studied in their natural environment for a significant period of time. Dr. Di Fiore has worked in South America studying primates for more than 25 years. He collaborates with a large group of graduate students, assistants, and fellow academics, many of whom are from primate habitat countries in South and Central America (Brazil, Ecuador, Colombia, Peru, and Mexico). He and his colleagues spend long stretches of time in the field following monkeys and collecting behavioral data. They track several different species of primates, including woolly, spider, titi and saki monkeys, using radiotelemetry, and they collect fecal samples for genetic, hormonal, and parasitological analysis. In the lab, Dr. Di Fiore and colleagues also investigate a number of broader questions concerning the evolutionary history, social systems, and ecological roles of various New World primates using molecular genetic approaches.

Because the primates Dr. Di Fiore studies live in a remote part of the Amazon, there were not many studies of these species prior to Dr. Di Fiore’s work. He and his team’s early research focused on describing the natural history and social lives of these animals. Now he and his team complement their field studies with molecular genetic laboratory work in order to address issues that are difficult to explore through observational studies alone, including questions about dispersal behavior, gene flow, mating patterns, population structure, and the fitness consequences of individual behavior.

Dr. Di Fiore and his team currently are focusing on two sets of species: ones living in small social groups where strong pair bonds sometimes form between individual males and females (titi and saki monkeys), and ones living in larger social groups, where the social core of the group is made up of related males (spider and woolly monkeys). Both of these systems serve as models for exploring different aspects of human behavioral biology.

Current research includes:

- Comparison of Parental Care Behavior in Titi and Saki Monkeys - Dr. Di Fiore’s comparative study of titi and saki monkeys, conducted in collaboration with Dr. Eduardo Fernandez-Duque of Yale University, is one of the longest-running field studies of either of these two primate taxa. Previously, saki behavior was virtually unknown. Both of these socially monogamous primates live in what are presumed to be nuclear family units, in which the male and female spend a lot of time together and co-operatively raise their offspring. This family structure is often considered a characterization of the human lineage. Among titis, males are nurturing individuals, carrying their offspring around soon after birth, and offspring often preferring to spend time with the father over their mother. Saki monkeys also live in small social groups, but there’s a difference in how mates are bonded to one another as well as in the level of male investment in care of their offspring. Dr. Di Fiore and his team recently discovered that saki monkeys do not always live in groups with just a single adult male and female; sometimes, additional adults of one or both sexes are present. Their social system is thus more dynamic and more variable than early naturalists’ reports imagined, with frequent turnover as new individuals move into the groups. The team is now performing laboratory work to see if pair mates in both of these species are actually the parents of the offspring born in that group. In many cases they are, but there are exceptions. Understanding the social systems of titi and saki monkeys provides insight into the origins of biparental offspring care, as well as the evolution and consequences of long term male-female social bonds, two feature of human social systems.

- Cooperative Behavior Among Male Spider Monkeys - Dr. Di Fiore and his team are studying on the cooperative and competitive relationships among males in spider monkey groups. For some time, primatologists have recognized that the grouping patterns and social structure of spider monkeys is remarkably similar to those seen some species of African apes, such as chimpanzees, despite only a very distant evolutionary connection between these taxa. For example, both spider monkeys and chimpanzees live in groups in which a set of presumably related males comprise the social center of their group. Males in these patrilineally-organized social systems engage in cooperative behaviors, such as patrolling and defending the boundaries of their territories and in collectively aggressing against males from other spider monkey communities. Despite their very aggressive social interactions with males from other groups, they can be extremely affiliative and cooperative with related males in their own social group. Dr. Di Fiore’s research has confirmed that male spider monkeys from the same social group are indeed often close relatives of one another, while females emigrate from their group of birth as they approach sexual maturity and join a new group. Within groups, multiple males sire offspring, and there’s no dominance hierarchy in which a single male fathers a disproportionate number of offspring. This mix of cooperative and competitive relationships among males parallels what is often seen in human small scale societies: bands of male relatives who are affiliative with each other, but act aggressively towards males of neighboring groups. Warfare and xenophobia are often considered very characteristic of humans, so this nonhuman model is used for understanding the origins of collective violence against unfamiliar mammalians.

- Influence of Reproductive Hormones on Sexual Behavior in Woolly Monkeys - Dr. Di Fiore and his team are studying the influence of female reproductive hormones on the development, social interaction, and mating behavior of woolly monkeys. Woolly monkeys live in large social groups with multiple males and females. Males are not overtly competitive or aggressive with one another over mating opportunities. Instead, when a female enters estrus, she solicits mating from many different males, some of whom are interested and others not. Dr. Di Fiore’s team is collecting observational data to see if females are selective about who they mate with and when and are exploring whether or not this strategy by females is a way to confuse paternity. In other primate taxa, females that mate with multiple males presumably do so to reduce the risk of their kids facing aggression from males they haven’t mated with, as well as getting some kind of investment in their offspring from more than one male. One of Dr. Di Fiore’s graduate students is currently conducting research that will determine whether females mate with males outside of the period of their cycle when they’re likely to conceive, the extent to which does female mating behavior corresponds with the likelihood of conception, and the frequency of mating by females across different phases of their reproductive cycles.

Bio

As a junior in college, Dr. Anthony Di Fiore took primatology classes with an inspiring professor who studied primates in the field. Those classes—which he considered the most interesting courses of his education—would later inspire his choice to become a primatologist. During a summer internship at the Duke University Primate Center (now the Duke Lemur Center), he studied the activity patterns of captive aye-ayes, nocturnal primates from Madagascar, and considered it an enriching and life-changing experience.

Dr. Di Fiore attended University of California, Davis for graduate school, where he worked with the mentor of his undergraduate professor. After his first year of graduate school, Dr. Di Fiore joined his advisor in Ecuador to begin a research project on wild woolly monkeys, and he fell in love with the country, the forest, and those primates. He has continued working with woolly monkeys ever since, expanding his research to include other species as well. He’s fluent in Spanish, thanks to both his mom for making him study it in high school and the local indigenous guides he worked with as he explored the forests of eastern Ecuador for a place to conduct his work.

There are 10 different types of monkey the live in the diverse rainforest where he now works, in the Yasuní Biosphere Reserve in lowland, Amazonian Ecuador. When he first started working in this area, it was more remote, and his interest was in seeing animals in their pristine environments. While many primatologists work with animals in human-impacted environments, Dr. Di Fiore found that working in a less developed site provided him an opportunity to collaborate with researchers working in more anthropogenically-modified habitats in order to compare the behavior between the two. Some of his students in Colombia are currently studying how human-modified habitats impact the dispersal abilities, behavioral biology, and genetic structure of primate species.

Dr. Di Fiore currently spends two to three months a year at his field site, spending time there in both the winter and summer seasons. There are not many places in Amazonia that are as untouched as this forest, but it now faces significant conservation challenges as it is at risk of development from logging, mining, and petroleum interests. He finds that researchers’ presence in pristine field sites is important for raising awareness of the importance of biodiversity conservation across the Amazon ecosystem.

At the University of Texas, Dr. Di Fiore directs the Primate Molecular Ecology and Evolution Laboratory, a state of the art genetics and genomics lab that generates molecular data to complement his team’s field data on behavior and social interactions.

Outside of the lab, Dr. Di Fiore enjoys being in the outdoors. He loves that he spends months of the year in a tropical forest, where he can hike and explore. When he’s not following monkeys, he enjoys exploring the trails and looking at the diverse biota that includes more than 600 species of birds, dozens of species of mammals, and hundreds of species of plants.